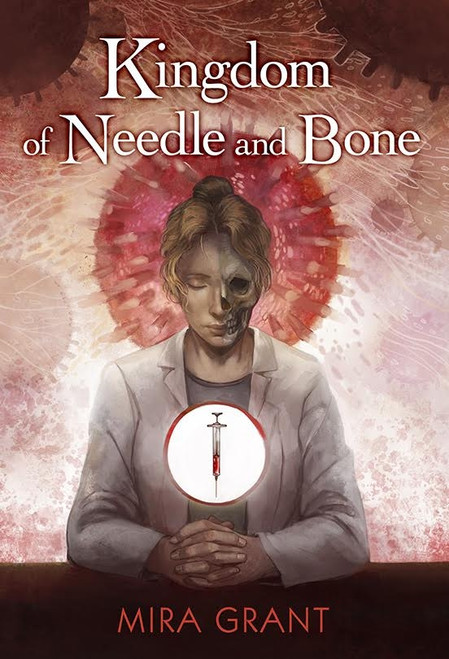

Dust jacket illustration by Julie Dillon.

We live in an age of wonders.

Modern medicine has conquered or contained many of the diseases that used to carry children away before their time, reducing mortality and improving health. Vaccination and treatment are widely available, not held in reserve for the chosen few. There are still monsters left to fight, but the old ones, the simple ones, trouble us no more.

Or so we thought. For with the reduction in danger comes the erosion of memory, as pandemics fade from memory into story into fairy tale. Those old diseases can’t have been so bad, people say, or we wouldn’t be here to talk about them. They don’t matter. They’re never coming back.

How wrong we could be.

It begins with a fever. By the time the spots appear, it’s too late: Morris’s disease is loose on the world, and the bodies of the dead begin to pile high in the streets. When its terrible side consequences for the survivors become clear, something must be done, or the dying will never stop. For Dr. Isabella Gauley, whose niece was the first confirmed victim, the route forward is neither clear nor strictly ethical, but it may be the only way to save a world already in crisis. It may be the only way to atone for her part in everything that’s happened.

She will never be forgiven, not by herself, and not by anyone else. But she can, perhaps, do the right thing.

We live in an age of monsters.

Limited: 1250 signed numbered hardcover copies

From Booklist (Starred Review):

“Thrilling and chilling, this all too plausible novella is less science fiction and more a nightmarish extrapolation of current medical trends.”

From Publishers Weekly:

“[Grant] brings an infectious new horror to life in this terse novella… Terrifyingly foreboding, peppered with news releases and sections of testimonies, this scathing critique of the anti-vaccination movement hints at a dark future ahead. Readers will be pulled along even as they try to look away.”

From Kirkus Reviews:

“The pseudonymous Grant (Feedback, 2016, etc.) writes with a lean urgency, taking barbed aim at the anti-vaxxer movement and its surrounding ethics while bolstering her potent cautionary tale with enough scientific factoids to make the whole rolling disaster terrifyingly plausible. Readers will be simultaneously relieved and disappointed when the novella ends, but as Grant makes perfectly clear, this is a fight that is never truly over. A thoughtful nightmare for uncertain times.”

From Locus:

“It’s a strong story, well told… The story is dark, and there’s a very strong undertone of examining the true nature of the Hippocratic Oath (‘First, do no harm’) in a world with eight billion people in it. Is letting some people die doing harm?”

From Library Journal:

“This briskly plotted novella takes a hard and horror-filled look at the vaccination debate, letting readers see a path to the future. Grant (“Newsflesh” series) dives into science and ethics, creating a story that lingers long after the last page is turned.”

From Kirkus Online:

“Readers can also look beneath the surface of the story to find a fascinating examination of the vaccination controversy, or more accurately the impact of the misinformation surrounding vaccinations and the delicacy of a successful ‘herd immunization.’ … It's those kinds of thought-provoking ideas that linger with readers and best exemplify what science fiction can do.”

Kingdom of Needle and Bone (excerpt)

“…people want to make this about politics: want to pretend there aren’t consequences for choosing not to immunize a child. After all, if everyone else immunizes, their children won’t get sick, right? The vaccine will protect the immunized children, and the unimmunized will remain pure, untouched by the filthy manmade miracle of modern medicine. Their bodies will be lowered into their graves devoid of the imaginary poisons that have replaced smallpox and polio and measles as the bogeymen haunting a parent’s heart.

That isn’t how herd immunity works. That isn’t how vaccination works. That isn’t how being part of a compassionate society works. Even setting aside the risk to the children whose parents choose to not to vaccinate—and as a medical professional, uttering the phrase ‘setting aside the risk to children’ breaks my heart—even taking that terrible, monstrous step does not protect our most vulnerable populations from a violent crime disguised as a personal choice. How dare you. How dareyou.”

—excerpt from op-ed by Dr. Isabelle Gauley, The Concord Times.

Part I: Ring Around the Rosies

1: Patient Zero

Lisa Morrishad been vaccinated according to her pediatrician’s recommended schedule, receiving her first dose of synthesized protection from the dangers of the world when she was two months old. Her parents had asked questions about each shot. They were scientifically-minded people who listened to their doctor, believing that years of medical school held more value than afternoons on Wikipedia, and they had approved the injections, one after the other, allowing their beloved daughter to build the most robust immune system possible.

Lisa had never been a fan of getting shots—what child was? What adult was, for that matter? An injection is an injection, no matter how great the potential rewards—but she had always enjoyed the ice cream that followed, and once she was old enough, she had learned to enjoy the subtle untensing of her parents’ shoulders. She was still young, eight years old, and sheltered enough not to understand everything that was happening in the world around her. She knew that some of the kids she went to school with didn’t get their shots, because of what they called a “personal exemption,” which was supposed to be about believing in God and thinking He would make everything better, even when that wasn’t true.

“If you don’t want them poking you with a needle anymore, all you have to say is you believe in Jesus and that makes it a sin,” one of the girls in Lisa’s class had said, smugly superior in her ability to beat the system.

Lisa, who understood Jesus the same way she understood Santa Claus—as a distant, powerful, potentially fictional figure who nonetheless had good things to teach about generosity and honesty and compassion—had frowned, and asked, “Would Jesus want me to lie?”

“Pretty sure Jesus doesn’t want us getting poked with needles,” the girl had replied.

Lisa had gone home, and thought a lot about Jesus and what He might want, and had come to the conclusion that if He existed, He wouldn’t want her to use Him to tell lies to her parents. She had not claimed religion. She had received her flu shot, the same way she always did, and when the girl in her class missed two whole weeks of school and had to stay into the summer to make up the time, Lisa had done her best not to be smug about it. Lying to Jesus did not, it seemed, pay.

That had been months ago, at the start of vacation. Now September was looming, and with it would come another year of math problems and essays and people standing outside her aunt’s practice with signs, chanting about how they had the right to make their own choices about their own children. It was sort of funny how some parents acted like kids couldn’t make up their own minds or make their own decisions, but could still get in trouble for doing stuff. Lisa sort of thought it was wrong, for parents to act like they were and weren’t people at the same time, and all because they were young.

Mostly, though, Lisa thought she didn’t feel good. Her mouth was dry and her nose was running and her head was spinning and her skin felt like it was two sizes too small, like she was going to burst out of it if she moved too quickly. She scowled at her reflection in the bathroom mirror of the hotel room she was sharing with her parents. They were probably going to say she’d spent too much time in the sun and if she was going to be sick, they’d be better off staying at the hotel and letting her rest, rather than turning it into sunstroke. And maybe they’d be right, but this was the endof the summer, and they were flying home from Florida tomorrow. If she wanted to ride the big coasters one more time, it had to be today.

Had she been older than eight, she might have understood that the kind of unwell she was feeling wasn’t normal, wasn’t sunstroke, wasn’t something she should hide. Had she been younger than eight, she might have gone whining to her mother before she realized that she ran the risk of cancelling the day’s adventure. Had she been any other age, she would still have died, but she might not have taken quite so many people with her.

- artists_list:

- Julie Dillon

- authors_list:

- Mira Grant

- binding:

- Hardcover

- book_case:

- None

- book_edition:

- Limited

- book_length:

- 128 pages

- book_type:

- Novella

- country_of_manufacturer:

- United States

- isbn:

- 978-1-59606-871-1

- is_subpress:

- Yes

- manufacturer:

- Subterranean Press

- print_status:

- Out of Print

- year:

- 2018