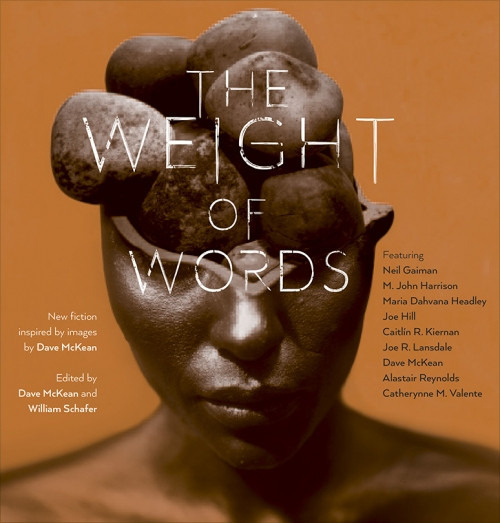

The consummate artistry of Dave McKean has permeated popular culture for more than thirty years. His images, at once bizarre, beautiful, and instantly recognizable, have graced an impressive array of books, CDs, graphic novels, and films. In The Weight of Words, ten of our finest contemporary storytellers, among them the artist himself, have created a series of varied, compelling narratives, each inspired by one of McKean’s extraordinary paintings. The result is a unique collaborative effort in which words and pictures enhance and illuminate each other on page after page.

The volume opens with Alastair Reynolds’s “Belladonna Nights,” set in the world of his novel, House of Suns, the ultimately poignant portrait of a thousand nights-long “reunion” held in the far reaches of space. Elsewhere in this generous book, we find a series of lovingly crafted tales featuring, among other elements, doppelgangers, lost souls and lucid dreamers. Highlights include Joe R. Lansdale’s “Robo Rapid,” a near future cautionary tale about Man vs. Machine; M. John Harrison’s “Yummie,” in which a middle-aged man experiences the hallucinatory aftermath of a heart attack; Joe Hill’s “All I Care About Is You,” the account of a pure, if temporary, friendship; Catherynne M. Valente’s extraordinary “No One Dies in Nowhere,” a tale of death and detection in the afterlife; Maria Dahvana Headley’s “The Orange Tree,” the story of an 11th century golem that is also a profound study of loneliness; and “Monkey and the Lady,” an ironic creation myth by the artist’s longtime friend and creative associate, Neil Gaiman. Together with “Train of Death,” an abbreviated account of the literal death of literature, this is one of two new stories by the always remarkable Gaiman.

The Weight of Words is the rare anthology that really does offer something for everyone. Its complementary merger of words and images adds up to something special, something more than the sum of its impressive parts. It is both a major accomplishment in itself and a long overdue tribute to an important—and necessary—artist.

The Weight of Words contains more than two dozen illustrations by Dave McKean, and is printed in two colors throughout.

Lettered: 26 signed numbered copies, specially bound, housed in a custom traycase

Limited: 350 signed numbered copies, bound in leather

Trade: Fully cloth-bound hardcover edition

From The New York Times:

“Offering a more traditional, but no less impressive, relationship between art and prose, THE WEIGHT OF WORDS is a stunningly produced anthology of original fiction inspired by the work of Dave McKean… Many anthologies are organized around a stated theme, but few are organized around a mood; what most impressed me about ‘The Weight of Words’ was its sustained core of loneliness, memory and loss across extraordinarily different styles of storytelling, from the sinuous far-future elegance of Reynolds’s ‘Belladonna Nights’ to the sharp, fragmented opacity of Sinclair’s ‘Broken Face.’ Every piece felt steeped in the sepia tones of McKean’s unsettling art… The caliber of fiction here is genuinely remarkable.”

From Publishers Weekly (Starred Review):

“McKean’s storied career as an illustrator, comics creator, and fine artist is the basis for this magnificent anthology, which contains 12 stories inspired by specific McKean images (all of which are included), as well as a short McKean comic. High points include Catherynne M. Valente’s stunning “No One Dies in Nowhere,” a mystery told in Valente’s characteristically lush prose with the precise discipline of a classical tragedy; Alastair Reynolds’s poignant “Belladonna Nights,” science fiction set in a far future in which the many scattered offshoots of a single personality hold reunions every 200,000 years; and Maria Dahvana Headley’s erudite “The Orange Tree,” a golem story set in 11th-century Andalusia. The collection also includes wonderful, intricate pieces from M. John Harrison, Caitlín R. Kiernan, and Iain Sinclair.”

Table of Contents:

- The Weight of Words — Dave McKean

- Belladonna Nights — Alastair Reynolds

- The Orange Tree — Maria Dahvana Headley

- Monkey and the Lady — Neil Gaiman

- No One Dies in Nowhere — Catherynne M. Valente

- Objects in the Mirror — Caitlin R. Kiernan

- Yummie — M. John Harrison

- Robo Rapid — Joe R. Lansdale

- The Language of Birds — Dave McKean

- Broken Face — Iain Sinclair

- All I Care About is You — Joe Hill

- The Train of Death — Neil Gaiman

A Few Story Excerpts

Belladonna Nights

Alastair Reynolds

I had been thinking about Campion long before I caught him leaving the flowers at my door.

It was the custom of Mimosa Line to admit witnesses to our reunions. Across the thousand nights of our celebration a few dozen guests would mingle with us, sharing in the uploading of our consensus memories, the individual experiences gathered during our two-hundred thousand year circuits of the galaxy.

They had arrived from deepest space, their ships sharing the same crowded orbits as our own nine hundred and ninety nine vessels. Some were members of other Lines—there were Jurtinas, Marcellins and Torquatas—while others were representatives of some of the more established planetary and stellar cultures. There were ambassadors of the Centaurs, Redeemers and the Canopus Sodality. There were also Machine People in attendance, ours being one of the few Lines that maintained cordial ties with the robots of the Monoceros Ring.

And there was Campion, sole representative of Gentian Line, one of the oldest in the Commonality. Gentian Line went all the way back to the Golden Hour, back to the first thousand years of the human spacefaring era. Campion was a popular guest, always on someone or other’s arm. It helped that he was naturally at ease among strangers, with a ready smile and an easy, affable manner—full of his own stories, but equally willing to lean back and listen to ours, nodding and laughing in all the right places. He had adopted a slight, unassuming anatomy, with an open, friendly face and a head of tight curls that lent him a guileless, boyish appearance. His clothes and tastes were never ostentatious, and he mingled as effortlessly with the other guests as he did with the members of our Line. He seemed infinitely approachable, ready to talk to anyone.

Except me.

The Orange Tree

Maria Dahvana Headley

Shelter me in your shadow

Be with my mouth and my word

Watch over my ways

So I will not sin again with my tongue.

—Solomon ibn Gabirol, 11th century

1.

Since the beginning of the world, there’ve been a thousand ways invented to be lonely. In a market stall, surrounded by speechless wooden wares, or banished to a black rock in the center of the sea. In a tower, feet forced into standing, floor too small for kneeling down, the only view a high window, the world below made of fire. On a road, parched, nothing but horizon. In the dark, visited by spirits jealous with their leavings.

At the tops of certain mountains there are places for those the world refuses, and at the bottoms of other mountains there are prisons for those the world regrets. There have been boulders installed for leapers once the never is too much.

The quiet is never quiet, not to the lonely. The quiet is full of newborn babies crying and lovers murmuring. The quiet is full of wineglasses and whippoorwills. Screaming quiet is the way the world lets a man know he’s alone forever, with no remedy but death or sorcery.

No One Dies in Nowhere

Catherynne M. Valente

First Terrace: The Late Repentant

There is a clicking sound before she appears, like a gas stove before it lights. One moment there is nothing, the next there is Pietta, though this is the last gasp of before/after causality in her pure, pale mind. Now that she is here, she will always have been here. Charcoal-blue rags twist and braid and drape around her body more artfully than any gown. A leather falcon’s hood closes up her head but does not blind her; the eyecups are a fine bronze mesh that lets in light. Long jessies hang from her thin wrists. This room which she has never seen belongs to her as utterly as her eyes: a monk’s cell, modest but perfect and graceful. Candles thick as calf-bones. Water in a black basin. A copper rain barrel, empty. She runs her hand along the smooth, wine-dark stone of her walls; her fingertips leave phosphor-prints. She lays down on her bed, a shelf for holding Piettas carved out of the rock, mattressed in straw and withered, thorny wildflowers that smell of the village where she was born. From the straw, she can look out of three slim glassless windows shaped like chess bishops. A grey, damp sky steals in, a burgling fog climbing up toward her, a hundred million kinds of grey swirling together, and the stars behind, waiting. Pietta remembers the feeling of the first day of school. She goes to the window and looks out, looks down. Her long hair hangs over the ledge like two thick vines. Black, seedless earth below, dizzyingly far. As close as spying neighbors across a shared alley, a sheer, knife-cragged mountain stretches up into the dimming clouds and disappears into oncoming night. The mountain crawls with people. Each carries a black lantern half as tall as they. A man with a short, lovely beard chokes on the smoke puking forth from his light, but even as he chokes,, he holds it closer to his mouth, desperate to get more. Their eyes meet. Pietta holds up her hand in greeting. He opens his jaw far wider than any bone allows and takes long, sultry bites out of the smoke.

When she turns away, a bindle lies on her bed of stone and straw. A plain handkerchief knotted around a long, burled black branch. She looses the cloth. Inside she finds a wine bottle, a pair of scissors, a stone figure of a straight-backed child in a chair, a brass key, a cracked, worn belt with two holes torn through, and a hundred shattered shards of colored glass. Pietta picks up one of the blades of glass and holds it to her breast until it slices through her skin. The glass is violet. The blood never comes.

Objects in the Mirror

Caitlín R. Kiernan

Ere Babylon was dust

The Magus Zoroaster, my dead child,

Met his own image walking in the garden.

—Percy Bysshe Shelley, Prometheus Unbound

1.

If I were writing a screenplay, I would begin, I think, with a fade in to a psychiatrist’s office. The walls would be that pale shade of blue that puts me in mind of swimming pools, and the sofa where the psychiatrist’s patients (she calls them clients) sit would be upholstered in the same shade, as would be the dingy low-pile polyester carpeting. I would note that time and friction have worn the arms and cushions of the sofa thin and shiny. There would be – are – framed photographs on the wall, oddly generic seascapes that mirror the walls and the sofa and are no doubt intended to instill a sense of serenity. There’s a bookshelf and a small table, and on the table is a box of Kleenex, a silver metal starfish, and a polished nautiloid fossil from the Devonian of Morocco. The psychiatrist’s desk is fastidiously neat. There are several careful stacks of papers, a few professional journals (The American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatry Research, and BJPsych), a copy of the 69th edition of the PDR, a tiny hourglass, a phone, a coffee mug filled with pens, and an electric pencil sharpener shaped like a robotic dog – a small concession to whimsy. There are two windows letting the wan January light into the room, one facing east, the other facing south. The curtains are drawn shut, muting the day. They’re a slightly paler blue than the walls, the sofa, and the carpeting. It may be that the sun has faded them. There are fluorescent bulbs in white recessed fixtures set into the dropped ceiling, a stark counterpoint to the afternoon sunlight. On the desk, there’s an iPod dock with speakers, but no music is playing at the moment. For now, the only sound is the psychiatrist tap-tap-tapping the eraser end of her No. 2 Ticonderoga pencil against the edge of her spiral-bound notebook. That and the sound of traffic out on the street.

The set decorator and prop master have hit the proverbial nail on its head. There is an almost archetypal tawdriness about the office, clinical prefab ennui; it pulses with the migraine thrum of a low-grade despair. If you weren’t suicidal when you showed up for your four p.m., you very well might be by the time the psychiatrist glances at her wristwatch (Daniel Wellington 056DW Classic Southhampton) or the clock mounted on the wall (Ikea) to remind you “our hour is almost up.” The air smells sickeningly of fake flowers, thanks to a “blooming peony and cherry” Glade plugin®. The door is shut and locked. It’s impossible not the think of Lucy van Pelt: The Doctor is In/Out. 5¢.

Robo Rapid

Joe R. Lansdale

When I unwound the cloak it was heavy and wide, having belonged to my father and being made to accommodate his size. I laid on half of it and folded the other half over me, covering my head against the blowing sand. If I was lucky, the sand wouldn’t cover me so deep I would smother. Even though the night air was chill, I was warm beneath the fold of the cloak. My smaller bag of items rested beneath my head for a pillow. I watched the stars until I fell asleep.

I was two days out, and so far I had only found more sand, and as morning came and the sun shone bright, I could see the air was decorated with thin lines of sand that seemed to hang in the air like a beaded curtain.

I thought of the bad things that had brought me here, and for a moment I wished I hadn’t come, that I had stayed with Grandfather back on the Flatlands. But that thought passed. Somewhere out there were my brother and sister, and I planned to find them.

So far, I hadn’t found squat and I had sand in my teeth.

All I Care About is You

Joe Hill

Limitation makes for power. The strength of the genie comes of his being confined in a bottle.

—Richard Wilbur

1.

She grabs the brake and power-drifts the Monowheel to a stop for a red light, just before the overpass that spans the distance between bad and worse.

Iris doesn’t want to look up at the Spoke and can’t help herself. The habit of longing is hard to quit and there’s a particularly good view of it from this corner. She knows by now certain things are out of reach, but her blood doesn’t seem to know it. When she allows herself to remember the promises her father made a year ago, her blood seems to throb inside her with excitement. Pitiful.

She finds herself staring up at it, that jagged scepter of steel and blued chrome lancing the dingy clouds, and hates herself a little. Let that go, she tells herself with a certain contempt, and forces herself to look away from the Spoke, to stare blindly ahead. Her idiot heart is beating too fast.

Iris doesn’t notice the not-alive not-dead boy watching her from the corner. She never notices him.

He always notices her. He knows where she’s been and where she’s going. He knows better than she knows herself.

2.

“Got you something,” her father says. “Close your eyes.”

Iris does as she’s told. She holds her breath, too. And there it is again, that thrill in the blood. Hope—stupid, childish hope—fills her like a trembling, fragile soap bubble, effervescent and weightless. It feels like it would be a terrible jinx to even allow herself to think the word: Hideware.

She isn’t going to the top of the Spoke tonight, she knows that. She isn’t going to be drinking Sparklefroth with her friends on the top of the world. But maybe the old man has a trick up his sleeve. Maybe he had a couple tokens socked away for an important day. Maybe the former Resurrection Man has one more miracle to work. Her blood believes all these things might be possible.

He sets something heavy in her lap, something far too heavy to be Hideware. That fantastic bubble of hope pops and collapses inside her.

“Okay,” he says. “You c-can look.”

His stammer disturbs her. He didn’t stammer BEFORE, didn’t stammer when he was still with her mother and still in the Murdergame. She opens her eyes.

He didn’t even wrap it. It’s something the size of a bowling ball, shoved in a crinkly bag. She peels the sack open and looks down at a cloudy emerald globe.

“Crystal ball?” she asks. “Oh, Daddy, I always wanted to know my future.”

What tripe. She doesn’t have a future…not one worth thinking about.

The old man leans forward on his bench, hands clasped between his knees so they won’t tremble. They didn’t tremble BEFORE either. He sucks a liquid breath through the plastic tubing up his nose. The respirator pumps and hisses. “There’s a m-mermaid in there. You’ve wanted one since you were small.”

She wanted a lot of things when she was small. She wanted Microwing shoes so she could run six inches off the ground. She wanted gills for swimming in the underground lagoons. She wanted whatever Amy Pasquale and Joyce Brilliant got for their birthdays, and her parents always saw that it was so, but that was BEFORE.

Something swishes, takes a slow turn in the center of the spinach colored sludge, then drifts to the glass to gaze up at her. She is so repulsed by the sight, she almost shoves the sphere out of her lap.

“Wow,” she says. “Wow. I love it. I really did always want one.”

He bows his head and squeezes his eyes shut. A tingle of shock prickles across her chest. He’s about to cry.

“I know it isn’t what you wanted. What we t-t-talked about,” he says.

She reaches across the table and clasps his hand, feels like she might start to cry herself. “It’s perfect.”

Only she’s wrong. He wasn’t struggling against tears. He was fighting a yawn. He surrenders to it, covers his mouth with the back of his free hand. He doesn’t seem to have heard her.

“I wish we could’ve done all the things we talked about. The S-sp-spuh-Spoke. R-Ride in a big buh-b-bubble together. These fuckin’ medical Clockworks, kid. They’re like hyenas pulling apart the corpse for the last goodies. The medical Clockworks ate your b-birthday c-cake this year, kiddo. We’ll see if I can’t do a little better for you next year.” He shakes his head in a good humored way. “I have to c-c-crap out for a while. A man c-can only take so much excitement when he’s g-got half a working heart.” He opens his eyes to a sleepy squint. “You know about m-mermaids. When they fall in love, they sing. Which I understand. Same thing happened to me.”

“It did?” she asks.

“After you were b-born,” he turns sideways, stretches himself out on the bench, struggles with another yawn, “I sang to you every night. Sang until I was all sung out.” He shuts his eyes, head pillowed on a pile of grubby laundry. “Happy birthday to you. Happy b-birthday to you. Happy b-b-b-buh-birthday sweet Iris. Hap-p-puh-p-p—” he inhales, a wet, clogged, struggling sound, and begins to cough. He thumps his chest a few times, turns his face away from her, shrugs, and sighs.

He is asleep by the time Iris reaches the top of the ladder, climbing out of his pod and leaving him behind.

She shuts the hatch, one of eight thousand in the great, dim, clammy, cavernous hive. The air smells of old pipes and urine.

Iris left her Monowheel next to her father’s pod on a mag-lock, because here in the Hives, anything that isn’t bolted down will vanish the moment you take your eyes off it. She climbs up onto the big red leather seat of her ’wheel and flips the ignition four or five times before realizing it isn’t going to start. Her first thought is that somehow the battery has gone dead. But it hasn’t gone dead. It’s just gone. Someone yanked it out of the vapor-drive and strolled off with it.

“Happy birthday to me,” she sings, a little off-key.

- artists_list:

- Dave McKean

- authors_list:

- Neil Gaiman

- binding:

- Hardcover

- book_case:

- None

- book_length:

- 248 pages

- book_type:

- Anthology

- country_of_manufacturer:

- United States

- isbn:

- 978-1-59606-825-4

- is_subpress:

- Yes

- print_status:

- In Print

- year:

- 2017