all ebooks sold through our website are DRM-Free and in epub format

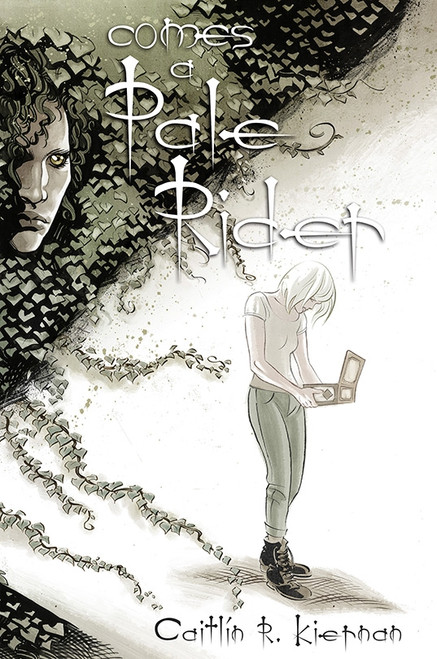

Cover illustration by Ted Naifeh.

Possibly Caitlín R. Kiernan’s most enduring character, albino monster slayer Dancy Flammarion has been carving a bloody swath across the American South ever since her first appearance in Threshold (2001), “laying the bad folks low.” In 2006, Subterranean Press published a World Fantasy Award-nominated collection of Dancy Flammarion short stories, Alabaster, and beginning in 2012, Dark Horse Comics released a three-volume graphic novel series introducing Dancy to comics in Alabaster: Wolves (winner of the Bram Stoker Award), Alabaster: Grimmer Tales, and Alabaster: The Good, the Bad, and the Bird.

And now, with Comes a Pale Rider, Kiernan offers a second collection of Dancy Flammarion short stories. From Selma, Alabama to the back roads of Georgia to a South Carolina ghost town, Dancy continues her holy war with the beings of night and shadow, driven always on by her own insanity or an angel with a fiery sword—or possibly both.

Comes a Pale Rider includes two new tales available nowhere else, each more than 10,000 words: “Dreams of a Poor Wayfaring Stranger,” and “Requiem.” The volume concludes with a brand new 3,000 word afterword.

Each of the stories features a full-page black-and-white illustration by Ted Naifeh.

From Publishers Weekly (Starred Review):

“Albino demon hunter Dancy Flammarion, who last appeared in the graphic novel Alabaster: The Good, the Bad, and the Bird, cuts a righteous swath across the American South guided by a skeletal, four-headed angel in this spectacular collection of five weird tales from Stoker Award winner Kiernan… Readers won’t have to be familiar with Kiernan’s earlier works to fall in love with her scrappy, mildly unhinged heroine or the masterful way in which she places charm and chills side by side.”

Table of Contents:

- Bus Fare

- Dancy vs. the Pterosaur

- Tupelo

- Dreams of a Poor Wayfaring Stranger

- Requiem

- Refugees (bonus volume, exclusive to the limited edition)

Comes a Pale Rider

(excerpts)

Bus Fare

She knows there was a town here once, because the deserted streets are lined with deserted, boarded-up buildings. The roofs of some have sagged and collapsed in on themselves, and one has burned almost to the ground. And if there were once a town here, there must have been people, too. So, she thinks, maybe only their ghosts live here now. She’s seen plenty of ghosts, and they usually prefer places living people have forsaken. These are the things the albino girl named Dancy Flammarion is thinking, these things and a few more, while the black-haired, olive-skinned girl talks. The girl is sitting on the wooden bench with Dancy. Her clothes are threadbare and she isn’t wearing any shoes. She might be fourteen, and she could pass for Dancy’s shadow. Dancy glances from her duffel bag to the faded bus sign, but she doesn’t look into the girl’s eyes. She doesn’t like what she’s seen there.

Dancy vs. the Pterosaur

Dancy Flammarion sits out the storm in the ruins of a Western Railway of Alabama boxcar, hauled years and years ago off rusting steel rails and summarily left for dead. Left for kudzu vines and possums, copperheads and wandering albino girls looking for shelter against sudden summer rains, shelter from thunder and lightning and wind. It’s sweltering inside the boxcar, despite the downpour, and, indeed, she imagines it might be hotter now than before the rain began. That happens sometimes, in the long Dog Day South Alabama broil. The floor of the boxcar is covered in dead kudzu leaves and rotting plywood, except a few places where she can see the metal floor rusted straight through. The rain against the roof sizzles loudly, singing like frying meat; she sits with her back to one wall, gazing out the open sliding doors at the sheeting rain.

Tupelo

The albino girl named Dancy Flammarion sits in the psychiatrist’s office, in a chair with one leg that’s shorter than the other three, so that it wobbles slightly whenever she happens to lean forward. Outside, it’s a bright day in late May, and while the psychiatrist talks Dancy half listens and watches as the sun spills in warm through the window, through the open slats of the plastic Venetian blinds, and traces a yellow-white path across the blue wall to her right. The wall with the door that leads out to the hallway and the receptionist and the waiting room and then the hallway that leads down a short flight of stairs and back into the real world. Dancy decided some time ago that the psychiatrist’s office isn’t precisely part of the real world, but is located, instead, in a crack between sleeping and wakefulness, between one dose of her meds and the next, between night and day. Between breaths and heartbeats. There is nothing about this room, she thinks, that has committed itself to being one thing or another; it never takes a side. Everything here exists between. But the sun, being an eye of God, can get in without an appointment. If the window were open, maybe other things could get in as well, things that know the trick of riding sunbeams – the noise of the traffic out on Highland Avenue, the sound of robins and blue jays singing, the footsteps and conversations of passing pedestrians. But the psychiatrist has never opened the window, and Dancy has begun to wonder if that’s even a possibility or if maybe the architects who designed this in-between place made it so the windows can’t ever be opened, not even by the psychiatrist.

“But you understand now that it’s only a dream? A dream and a hallucination?” the psychiatrist asks her, and Dancy looks away from the horizontal stripes of sunlight on the blue wall, blinking, looking back at the psychiatrist, trying to recall the answer that’s expected of her, the answer that will get her out of the room the quickest. “Animals don’t talk,” says the psychiatrist, prompting Dancy, because she has other crazy people to see before she can also leave the in-between place and go to wherever it is she lives when she isn’t here. Dancy wonders what awful sin the psychiatrist has committed that she’s condemned to spend five days a week here in the in-between place.

Dreams of a Poor Wayfaring Stranger

Behind her is all the fire that ever was, the righteous heaven-spun fire of the seraph that has burned down her life and scorched the summer sky white as bleached bones and melts the highway beneath Dancy Flammarion’s feet. The asphalt may as well be no more than licorice left too long in the sun, the way it sticks to the soles of her boots and slows her down, holds her back, a vast stripe of licorice and tar to divide the pines and the kudzu and the South Alabama day so that she cannot ever get lost in this wilderness and wander without even knowing her left from her right. She would look back over her shoulder at the firestorm, but she knows too well that it would blind her. It would burn the eyes from her skull and damn her to darkness for however long she has left to live. In this dream, it would do exactly that, no matter how many times her waking eyes have looked into that selfsame inferno with no more protection than a pair of shoplifted sunglasses and been left nothing worse than dazzled and aching. The day roars with the fire, and the sky crackles with it, and the very ground beneath her feet shudders as all the land behind her is washed in those merciless flames, as the day burns and burns and burns but never is consumed. Black vultures wheel above her, and crows, too. There are dead things all along the highway, the roadkill carcasses of possums and armadillos and coyotes, raccoons and deer, and she is very careful to step over or around all these broken, rotting bodies. The day simmers with the stench of decay and brimstone and melted pitch, and Dancy wishes that the scalloped shadow cast by her tattered black umbrella were a little more substantial. She wishes also there were a dark culvert somewhere nearby that she could climb down to and huddle inside until nightfall comes round again, concrete shadows that are not cool – because there is no genuine coolness left in this land, because the seraph has seen to that – but shadows that even stifling would still seem cool by comparison. There might also be a kindly trickle of creek water running through the culvert, and even warm it would seem like ice against her cracked lips and parched tongue. Sweat streaks her face and drips to the asphalt and sizzles and boils away to steam in an instant.

Requiem

(October 2018)

For half a night and most all of an autumn day, the blue-and-silver bus has ferried the slight, green-eyed woman along grey Southern highways beneath low-slung grey Southern skies. The bus left Savannah a little after midnight, departing the Greyhound station on Oglethorpe Avenue and rumbling north and west along the asphalt ribbon of I-16, racing the twin glare of its own headlights past Macon and a dozen other sleeping towns and all the way to Atlanta, farther north than the woman had ever been before. A six-wheeled carriage of diesel-scented steel passing through darkness to muddy daybreak to a rainy morning and then a stormy afternoon, before finally turning west and south towards Birmingham. Whenever the bus stopped – disgorging a few passengers, swallowing up a few others – the slight, green-eyed woman kept her seat, too afraid that if she were to dare get off, even just to stretch her legs for five minutes or have a cigarette or buy a bottle of Dr. Pepper, she’d never find the courage to get back on again.

And then where would I be? Why, then I’d be nowhere at all.

It took the better part of five years to find the courage to buy a ticket and pack a suitcase and board the night bus. When she was very young, she had imagined that she was brave and bold and audacious. When she had lived in the rotten, rambling mansion on East Hall Street with Miss Aramat Drawdes and the other ladies who’d styled themselves the Stephens Ward Tea League and Society of Resurrectionists, when she was hardly yet even nineteen years old, way back then she’d imagined herself just about the bravest, boldest, most audacious girl in the whole wide world. But way back then, way back twenty long years ago, what she’d known about the whole wide world would have fit in a brass thimble, with plenty of room left over for her or anyone else’s thumb. Back then, she’d called herself Isolde Penderghast, a name she’d found written on the back of an old photograph, and she had played at being a monster. They’d all of them played at monstrosity, the nine women who’d lived together in the ancient house, and they’d even been permitted to rub shoulders with monstrous things and do the bidding of monstrous things, only to learn too late that they themselves were nothing more than sadly preposterous imitations and that all the real monsters laughed at them whenever their backs were turned.

Refugees

(bonus volume excerpt)

The summer day is quickly fading down to dusk, and Dancy Flammarion stands in the shade of her tattered black umbrella exactly halfway across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, watching while the muddy, olive-colored Alabama River slides silently by a hundred feet below. Her mouth is parched as a long week without rain, but she manages to work up a thick little glob of saliva. She leans out over the guard rail and spits. She thinks, Sure, I expect I’ll never get to see the Gulf of Mexico for myself, but here you go, Mr. River. You just be so kind as to carry that speck of me on down to the sea.Cars and trucks roll past behind her, this old bridge ferrying four lanes of traffic in and out of the city of Selma since 1939 and in 1965, the Reverend Martin Luther King led twenty-five hundred men and women across it, this modest span of steel and reinforced concrete named in honor of a Confederate brigadier general and a grand dragon of the KKK. Dancy closes her eyes, shutting out the sun and the blistering sky, and for a time her world shrinks down to just the smell of the river and of asphalt so hot its gone soft and runny, to traffic noise and the shrill thrum of cicadas, and to the way the bridge shudders beneath its heavy load. Maybe I’m a bridge, too, she thinks, not sure where the thought is headed, but thinking it all the same. Maybe I’m just a different sort of bridge. There’s a sound from the sky, then, a long, slow rumble that might well have been thunder, though there isn’t a cloud in sight. But it’s always been easier for her to pretend she’s hearing thunder than admit what that rumbling sound really is. And there it is again, still louder than before, more insistent, impatient, unhappy at the way she’s frittering away the day when there’s so much work to be done.

- artists_list:

- Ted Naifeh

- authors_list:

- Caitlin R. Kiernan

- book_edition:

- ebook

- book_length:

- 209 pages

- book_type:

- Collection

- isbn:

- 978-1-59606-986-2

- is_subpress:

- Yes

- print_status:

- Digital

- year:

- 2020

- badge:

- eBook Edition