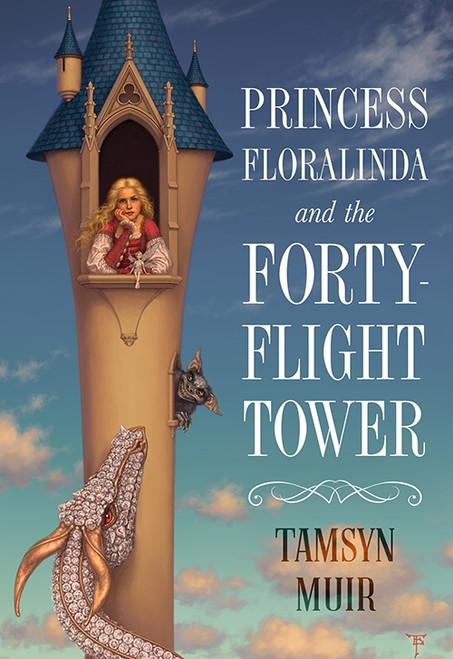

Dust jacket illustration by Tristan Elwell.

Breaking News: Due to popular demand, and because we have a sequel novella to Princess Floralinda and the Forty-Flight Tower under contract, we're going back to press for a second printing, which will be signed by the author!

We're pleased to present a very dark, very long (nearly 40,000 words) novella by the acclaimed author of Gideon the Ninth.

About the Book:

When the witch built the forty-flight tower, she made very sure to do the whole thing properly. Each flight contains a dreadful monster, ranging from a diamond-scaled dragon to a pack of slavering goblins. Should a prince battle his way to the top, he will be rewarded with a golden sword—and the lovely Princess Floralinda.

But no prince has managed to conquer the first flight yet, let alone get to the fortieth.

In fact, the supply of fresh princes seems to have quite dried up.

And winter is closing in on Floralinda…

Lettered: 26 signed leatherbound copies, housed in a custom traycase

Limited: 1500 signed numbered hardcover copies

From Publishers Weekly (Starred Review):

“Muir (Gideon the Ninth) showcases her distinctive voice in this playful page-turner that flips fairy tale archetypes on their heads... along the way Floralinda learns to fight, ask questions, and think for herself—none of which a princess is ‘meant’ to do. Told with the humor, whimsy, and innocent romance of a children’s story, this adult fairy tale is a winsome enchantment.”

Princess Floralinda and the Forty-Flight Tower

(excerpt)

Flight Forty, Again

A Visitor.

Floralinda slept for a very long time, though she had no way of measuring it. She woke to tiny sobs, each of which sounded like a delightful little bell being tinkled, or the tiniest trickle of a mountain stream.

She opened her eyes very slowly, as she also woke up to find that almost every inch of her poor body felt tremendously battered and bruised, and her hands sore beyond reckoning. It was like the day after she had learned to trot on her pony, only a thousand times worse. Floralinda did not sit up, but lay there listening to the sound: it was so beautiful and it was so sad, with both feelings mixed, that tears sprang into her eyes.

With a great deal of effort, she sat up. The storm had cleared, leaving only the tenderest of summer mornings, and a nice fresh smell to mask the sour illness one. The only sign that the tower had ever been rocked by thunder and lightning was a very sodden part of the rug where the storm had blown something through the window. On that sodden part, there was—a fairy!

It really was a fairy, and it looked exactly the same as fairies did in all of Floralinda’s picture-books. Then again, it might have been a pixie: she wasn’t quite sure of the overlap. Both kinds were depicted as tiny, beautiful persons with brightly-coloured butterfly wings, and sure enough this was a tiny beautiful person small enough to be comfortable in Floralinda’s hand. But none of her picture-books had ever depicted such a sorry example of Fairyland, this one being wet through, and quite tatty, and worst of all—

“Oh,” said Floralinda, moved to pity, having learned absolutely nothing about the veracity of children’s storybooks, “oh, you poor thing!”

Rather than butterfly wings, as illustrated, the fairy’s wings showed clearly as being rather like a cranefly or dragonfly’s, split into two pairs: long and transparent, with all the tiny veins showing through. The pair on the fairy’s rightmost side were fine, if a bit ragged, but the upper wing on the leftmost side had been torn to drooping shreds, and the lower wing was missing entirely.

The fairy, or the pixie, ceased its beautiful sobs and looked up at Floralinda. In the early morning light it was the same colour as a delicate white rosebud, with green and blue lights like the veins inside a petal (if you have pulled apart a rose-petal you will know what I mean). It had a pretty, plaintive sort of face, very delicate, and scarcely bigger than one of Floralinda’s old dolls that she pretended not to still play with. Everything about it had the air of an exceedingly well-done doll in a doll’s house, in fact, right down to the cunning thistledown skirts so wet through from the storm. The exquisitely tiny curls of hair had taken a wetting and, as they dried, stuck up like duck fluff. It is hard to describe the exact colour of that hair. It was a bit like what happens if you are very blonde and take a dip in the public swimming baths, and it takes on a greenish aphid tinge, from all the chemicals they use to keep the water clean.

The fairy said, in a surprisingly piercing voice for its size:

“Do you have a mother currently in hospital, and you’re feeling rather out of the way, and there are new little jackets everywhere, and your nurse isn’t paying you any attention, so you’ve run away from home to the bottom of the garden?”

“Pardon?” said Princess Floralinda.

The fairy repeated itself. Floralinda could answer in all honesty, No, not remotely; so the fairy pressed:

“Have you disappointed your grandmother by telling her that you don’t believe in fairies; and now you’re having an awful dream that you’re only about as big as a daisy-stem?”

Floralinda answered No again; and added that she was a princess, in case that helped the situation. The fairy mulled on that one for a while, and then said doubtfully, “Was I at your christening?”

“I don’t think so,” said Floralinda cautiously. “My aunt had a baby at around the same time and there was an argument about who got to use the christening dress, so my mother said she felt she had to be gracious because she was the Queen, and in any case it was a frightful expense and family only.”

“Then we have nothing to say to each other,” said the fairy.

Princess Floralinda, in a rush, tried to explain her situation; but the fairy sat there in the wet sunshine unmoved. “I am a bottom-of-the-garden fairy,” it said. “My area is nominally children who need to be taken to Fairyland and removed just in time for their mother to bring a new baby home. I’m going to get in terrible trouble for being here,” it added, somewhat passionately, “only each time you finish the job you have to find a new garden where exactly one child has been born, so I’m obliged to always be on the move. This whole business has been simply ruined by modern society. Children are so knowing right now. I wanted to be the fairy who put the underneaths of mushrooms on, or made buttercups able to reflect whether or not you liked butter, or something chemical and practical; but they said the industry was saturated, so here I am, at exactly the wrong time professionally; and I’m sure to get into a most dreadful bother, and nobody ever trusts me.”

At this point it stamped its little foot and started crying again, which was quite nice, as its voice was not so pretty as its little weeping sounds.

“But perhaps you could help me escape,” said Floralinda feebly, who had a pounding headache, and was feeling rather the worse for wear. “I am so tired of being in this tower. The dragon yells at all hours, and there were a great many princes but none of them did very much, and I’ve had very bad times with goblins, and I’m—so—lonely.”

Not having known how lonely she had been, Floralinda began to cry herself. It was not the great hysterical yowls of before, but an exhausted kind of lying-back-to-cry where the tears squeezed out of her eyelids. At this the fairy stopped its crying, displayed the first flicker of interest, and dragged itself over to her—finding it could not fly on one wing, it made a sort of hop-skip-jump attempt, and nimbly climbed up the remaining panels of silver gauze.

“Are you truly a princess?” it said.

“My mother is a queen and my father is a king,” said Floralinda sadly, “and what’s more, they’re even married to each other.”

“It’s just that the tears of a real princess can be very useful,” said the fairy, with the attitude of someone aware that they could be being rude. “Apart from being pearls if she’s good and frogs if she’s bad, I mean; they’ve got properties I understand to be solvent and even medically valuable. Of course I’m only an amateur.”

And—though Princess Floralinda was a bit outraged—the fairy reached forward, and took some of her tears, and applied them neatly to the broken wing. At the briefest application of princess tears, all the glass-like chambers of the wing seemed to run together, as if they had been held close to a flame, and the ripped-up parts were made whole again; but the lower part which had been ripped off did not grow back.

“Well,” said the fairy practically, “that’s something; perhaps if you could cry something other than tears of loneliness, it would be even better. Could you cry for a broken heart, do you think?”

Princess Floralinda thought she could not cry for a broken heart, certainly not on command. But the fairy had become a bit friendlier, and up close was certainly so pretty that it was hard to be angry. Such beautiful little features—such cunning little pointed ears and nails on each finger and toe—such eyes, iridescent, like the chips of opal in her grandmother’s rings. It said, “Then could I prevail upon you to carry me down to the bottom, or to lower me down on a string?”

As there was nothing in the room that could be lowered down any further than two or three flights at best, and as the difficulty of getting to the bottom was the problem whole and entire, Floralinda supposed not.

“There’s nothing for it,” the fairy said. “I shall have to wait to bathe in the light of the full moon, and we’ve just had one, so it will take weeks. The wing will grow back then, and by that point you will be gone, so at least I’ll have full use of the tower.”

A great hope seized Floralinda.

“Oh,” she gasped, “oh, do you really think that I will be gone?”

“Naturally, yes,” said the fairy. “Those are goblin bites on your hands, aren’t they? They’re quite infected. Goblins are filthy. You’ll be dead in a week.”

At Floralinda’s new bout of tears, the fairy said a bit diffidently, “Cheer up; you might die earlier.”

- authors_list:

- Tamsyn Muir

- binding:

- Hardcover

- book_case:

- None

- book_edition:

- Limited

- book_length:

- 200 pages

- book_type:

- Novella

- country_of_manufacturer:

- United States

- isbn:

- 978-1-64524-057-0

- is_subpress:

- Yes

- print_status:

- In Print

- year:

- 2020